CDC agrees: The national eviction crisis is a public health emergency

Last week, in a blog post headlined, “The national eviction crisis has arrived,” we detailed the sad reality that millions of Americans are now at dire risk of losing their homes. The primary reasons for this are COVID-19, the almost incomprehensible loss of jobs in the U.S., and the failure of Congress to approve comprehensive relief for renters and extend an eviction moratorium on federally backed housing.

But the eviction crisis is not just a crisis involving housing and homelessness. Turns out, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) it also constitutes a public health emergency. The CDC acknowledged in an order released Tuesday, Sept. 1 that 30 to 40 million evictions could occur this year and that those would result in tenants doubling up in overcrowded conditions or forced into unsafe shelters or the streets, all of which would encourage the spread of COVID-19. To prevent that, the CDC imposed a moratorium on evictions to last from Sept. 4 through Dec. 31, affecting all rental property that was not subject to broader protections in cities or states. The previous Congressionally-imposed moratorium expired by the end of August, and only affected tenants in federally backed or supported units.

Margie Hernandez is a 63-year-old widow in San Antonio. She moved her family into a Best Western after they were evicted in June. The Hernandez family had followed health guidelines before their eviction – they stayed at home and practiced social distancing. But in the hotel lobby, they were “packed in like sardines.” She and her children wore masks, but many guests didn’t. Several days after checking into the hotel, Margie Hernandez and one of her adult sons lost their sense of taste; they were subsequently diagnosed with COVID-19. Margie spent five days in intensive care and is still on oxygen. Her 27-year-old son remains on dialysis.

Margie Hernandez is a 63-year-old widow in San Antonio. She moved her family into a Best Western after they were evicted in June. The Hernandez family had followed health guidelines before their eviction – they stayed at home and practiced social distancing. But in the hotel lobby, they were “packed in like sardines.” She and her children wore masks, but many guests didn’t. Several days after checking into the hotel, Margie Hernandez and one of her adult sons lost their sense of taste; they were subsequently diagnosed with COVID-19. Margie spent five days in intensive care and is still on oxygen. Her 27-year-old son remains on dialysis.

Margie shared her story with Matthew Desmond, author of the acclaimed “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City.” Desmond recently wrote an opinion piece for The New York Times headlined, “The Rent Eats First, Even in a Pandemic.”

“During a pandemic that forcefully links our health to our homes, eviction will help spread the virus, as displaced families crowd into shelters, double up with relatives and friends, or risk their health in unsafe jobs to make rent or pay for moving expenses,” Desmond writes.

And COVID-19 is not the only health threat, Desmond notes. “Marshals that carry out evictions are full of suicide stories: the early morning rap on the door followed by a single gunshot from inside the apartment, the blunt sound of giving up. From 2005 to 2010, years when housing costs were soaring across the country, suicides attributed to eviction and foreclosure doubled.”

Experts (now including the CDC) warn that as many as 40 million U.S. households could face eviction by year’s end without federal action. These are unprecedented numbers; there have previously been about 900,000 evictions per year. Eviction rates already are on the rise.

Common stereotype has it that our nation’s greatest housing crises exist in “coastal” cities – places like New York City, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. But Desmond, who manages a project that tracks evictions, notes that cities with some of the highest eviction rates include Tulsa, Okla.; Albuquerque; N.M.; Indianapolis, Ind; Toledo, Ohio; and Baton Rouge, La., not to mention many suburban communities and small towns across the country. Tucson, Az. usually sees 10 to 30 eviction cases a day; in June, it handled 50 cases a day. That same month, eviction cases were up 70 percent in Alabama, compared with June 2019. And eviction filings were up 109 percent above average levels in Milwaukee.

The CDC’s new moratorium will delay the crisis, but it will not stop it without Congressional action to provide emergency rental assistance. Otherwise, once the moratorium expires again, tenants will find themselves with impossibly high arrearages to make up. The CDC order does not prevent this; it does not even prevent landlords from piling up late fees on top of the monthly rent owed.

Public health experts are concerned. At the beginning of August, 26 medical associations signed a letter urging Congress to provide housing resources to renting families, recognizing the housing crisis to be a health crisis. “As leaders in the health sector, we understand that now, more than ever, housing is health,” the letter states. “Without action from Congress, we are going to see a tsunami of evictions, and its fallout will directly impact the healthcare system and harm the health of families and individuals for years to come.”

Desmond concludes that the coming evictions won’t just make it more difficult to manage the coronavirus pandemic – they will also hinder efforts to rebuild our economy.

“Our efforts to defeat COVID-19 and recover from the economic damage it has wrought will be deeply compromised if we fail to help families keep their homes,” Desmond writes. “Besides pushing up coronavirus infection rates, the eviction crisis will also aggravate our unemployment crisis, as workers get displaced far from their jobs, and it will further complicate school re–openings, as evicted children, themselves at heightened risk of infection, shuffle from one school to the next.”

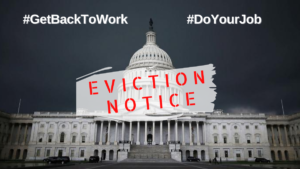

On May 15, the House of Representatives passed $100 billion in emergency rental assistance plus $11.5 billion to help the homeless within its HEROES Act. More than three months later, the Senate has not acted. So far Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has been unmoved by the looming dangers of massive evictions to tenants. Perhaps he will be more attuned to landlords who won’t want to forego rent through the end of the year.