Moving Backward: Efforts to Strike Down the Affordable Care Act Put Millions of Women and Girls at Risk

Editor’s note: The following essay is cross-posted with permission from the Center on American Progress (CAP). Co-Author Jamille Fields Allsbrook is the director of women’s health and rights for the Women’s Initiative at CAP. Co-Author Sarah Coombs is the senior health policy analyst at the National Partnership for Women & Families, a nonprofit, nonpartisan advocacy group dedicated to improving the lives of women and families by achieving equality for all women and focusing on issues that increase equity, health, reproductive rights, and economic justice.

By Jamille Fields Allsbrook and Sarah Coombs

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) guarantees women critically important consumer protections, including by prohibiting discriminatory insurance practices in pricing and coverage in the individual market. Before the law was enacted, women routinely were denied or charged more for coverage if insurers determined that they had a preexisting condition and, due to discriminatory gender rating practices, were often charged more solely on the basis of their gender. For example, in the individual insurance market, a woman could be denied coverage or charged a higher premium if she had a diagnosis of HIV or AIDS, lupus, or an eating disorder, among other conditions, or even if she had previously been pregnant or had a cesarean birth. Making matters worse, due to systemic racism and entrenched health disparities, women of color experience higher rates of certain chronic conditions—such as diabetes, cervical cancer, and asthma—that can lead to higher rates of coverage denial and higher premiums.

Thanks to the ACA, all women with preexisting conditions in the individual market are assured fair access to comprehensive and affordable health coverage. Unfortunately, recent efforts to repeal and undermine the law would put millions of women and girls once again at risk of being charged more or denied coverage.

The fate of the ACA is once again at stake, pending a decision from the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in the health care repeal lawsuit known as Texas v. United States. Texas and 17 other states—with support from the Trump administration—are challenging the ACA’s constitutionality, including its guaranteed issue provisions and community rating system. Without guaranteed issue protections, women could be denied coverage based on their medical history, their age, and their occupation, among other factors. Without community rating, they could be charged more, or priced out of the insurance market altogether, based on their health status or other factors. Moreover, if the entire ACA is repealed, insurance companies could try to reinstate gender rating, a common pre-ACA practice in which insurance companies charged higher premiums for women than they did for men.

If the court rules to strike down the entire ACA, there will be devastating consequences for everyone; but these negative outcomes will be most pronounced for the millions of women with preexisting conditions and, in particular, for women of color and women with low incomes, whose health and economic security would be most at risk.

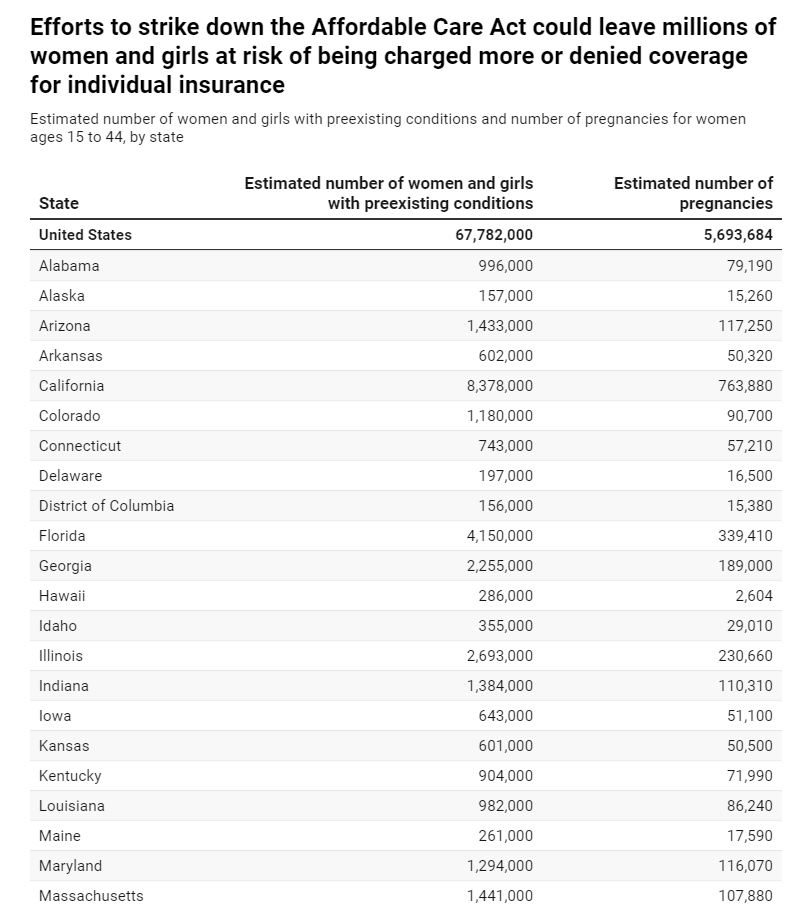

The authors of this column estimate that more than half of nonelderly women and girls nationwide—nearly 68 million—have preexisting conditions. There are also approximately 6 million pregnancies each year, a commonly cited reason for denying women coverage on the individual market before the ACA. The table below provides state-level detail for the number of women and girls with preexisting conditions and the number of pregnancies.

A large share of women have insurance through an employer or Medicaid, and therefore, their coverage would protect them from discriminatory practices such as medical underwriting or denials based on health conditions. But the data make clear that allowing insurers to return to pre-ACA practices could lead to millions of women and girls being denied coverage or charged more based on their health status if they sought coverage in the individual market.