2021 sets new mark for voter suppression laws; Texas threat still looming

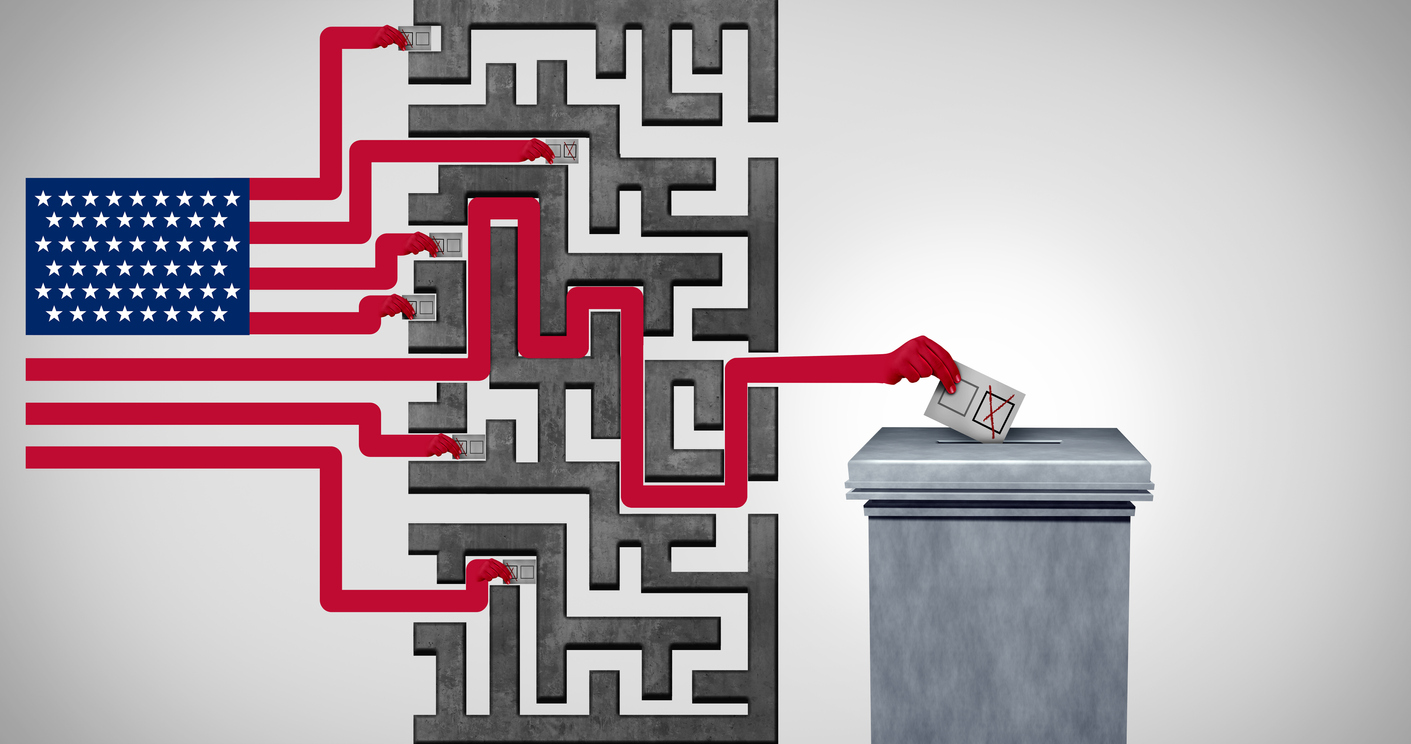

Calendar year 2021 is not even half over – yet we already know that it will set a modern-day record for the number of voter suppression laws passed by state legislatures and enacted into law in one year.

Between January 1 and May 14 of this year, 14 states enacted 22 new laws that restrict access to the vote. That breaks a record set in 2011, when – by October of that year – 19 restrictive laws were passed in 14 states.

“The restrictive laws from 2011 were enacted after the 2010 elections brought a significant shift in political control over statehouses — and as the country confronted backlash to the election of its first Black president,” writes the Brennan Center for Justice in a May 28 update. “Today’s attacks on the vote come from similar sources: the racist voter fraud allegations behind the Big Lie and a desire to prevent future elections from achieving the historic turnout seen in 2020.”

Between January 1 and May 14 of this year, 14 states enacted 22 new laws that restrict access to the vote

In April and May, Voices for Human Needs focused on voter suppression bills in Georgia and Florida – you can read those posts here and here. Today, we will examine perhaps the most onerous bill of all – Senate Bill 7, which failed to pass the Texas Legislature after a coalition of mostly Latinx and Black lawmakers walked off the House floor, denying the body a quorum and effectively shutting down legislative activity until the Legislature’s clock expired. Although lawmakers are now in recess, Governor Greg Abbott has pledged to call them back in special session later this year – perhaps as early as August. Democrats then will have little power to stop the GOP-dominated Legislature from passing voter suppression legislation.

Why is Senate Bill 7 so onerous? Because it plainly seeks to make it more difficult for minority voters to cast ballots – particularly in Harris County, which includes Houston, where many of the state’s Democrats reside.

Senate Bill 7 would ban two types of voting used by election administrators in Harris County in the 2020 election – drive-up voting and 24-hour voting. According to a Washington Post analysis, 130,000 voters in Harris County took advantage of drive-through voting and an additional 10,000 voters cast ballots during a 24-hour voting marathon the county offered in the final week before Election Day.

The Post reported that voters of color made up more than 50 percent of those who took advantage of drive-through voting and the 24-hour voting window. That was a higher percentage than minority participation in early voting overall in Harris County, when Black and Latinx voters accounted for just 38 percent of all voters. Senate Bill 7 also would ban early voting before 1 p.m. on Sundays – a move clearly aimed at stopping efforts by Black churches to encourage congregants to cast ballots right after services – a get-out-the-vote tactic often referred to as “souls to the polls.”

“Why in the world would you pick Sunday morning to outlaw voting in Texas, but for the fact that they know that a lot of Black parishioners historically have chosen that time to organize and go to the polls?” Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-Tex.) told the Post.

The Texas measure, like the new laws in Georgia and Florida, would make it more difficult to vote by mail, and would give new access to partisan poll watchers. Further, it would impose stiff new civil and criminal penalties on election administrators, voters, and those who seek to assist them.

And the Texas legislation sought to restrict community voter mobilization programs. It would require that anyone who drives more than two non-relatives to the polls who require assistance to submit a signed form stating the reason for the assistance. That means volunteer van drivers who provide transportation for churchgoing voters would have had to jump through the added hoop of submitting a signed document.

Voter rights advocates have singled out the new laws in Georgia and Florida, as well as the Texas proposal, as versions of “Jim Crow 2.0” — aimed squarely at racial minorities.

Cliff Albright, a co-founder of the group Black Voters Matter, told the Post that the comparison to Jim Crow is even more apt in the case of Senate Bill 7 because the language Republican lawmakers have used to justify it is eerily similar to how Southern racists blocked Black citizens from voting for decades:

“Then, as now, those in power denied racist intent, he noted. Then, as now, they claimed they wanted to protect the “integrity” of elections. Then, as now, they imposed restrictions that they claimed would apply to all voters but that in practice applied overwhelmingly to people of color.”

The Brennan Center reports that with close to one-third of legislatures still in session, additional restrictive measures are likely to pass, increasing the degree to which 2021 will set new, modern-day records when it comes to voter suppression.

But the news is not all bad. First off, legal challenges already have been filed in Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Iowa and Montana – and if anything resembling Senate Bill 7 eventually passes in Texas, it certainly will be subject to litigation as well. How successful legal challenges will be is not yet clear.

And second, the Brennan Center notes, many states are passing more expansive laws that make it easier to vote. The Center has tracked 28 such bills that have been signed into law in 14 states.

Just this week, Vermont Governor Phil Scott, a Republican, signed into law a measure that will require the mailing of ballots to every registered voter in the state, whether they request a ballot or not. In signing the law, which easily passed the General Assembly on a bipartisan 119-30 vote, Scott said he did so “because I believe making sure voting is easy and accessible, and increasing voter participation, is important.”

The action by Scott and Vermont Republicans – as well as bipartisan efforts to ease access to voting in states such as Kentucky – prove that improving our democracy need not be a partisan issue. People acting in good faith just need to stand up and be counted, Republican or Democrat or any other party. In fact, that would be a very good standard to hold the U.S. Congress to, since they have the power to adopt legislation to prevent some states from adopting harsh voter suppression laws while others take Vermont’s path. That would require a bipartisan 60 votes in the U.S. Senate, and there is no hint of that much bipartisanship in the Senate right now.