For state and local employees, a winter of discontent – and beyond – is approaching

When the reality of a coronavirus pandemic struck home last March, many state and local governments were quick to take action, slashing budgets and planning for painful layoffs and furloughs. The damage was mitigated, in part, by two factors: healthy, pre-pandemic economies, which meant more tax revenue coming in, and the CARES Act, which Congress passed last spring, and which provided $150 billion in state and local aid.

Still, 1.3 million public-sector jobs were lost during an eight-month period. Those jobs, for the most part, have not come back. And now, heading into the new year and beyond, state budget experts say things are about to get worse.

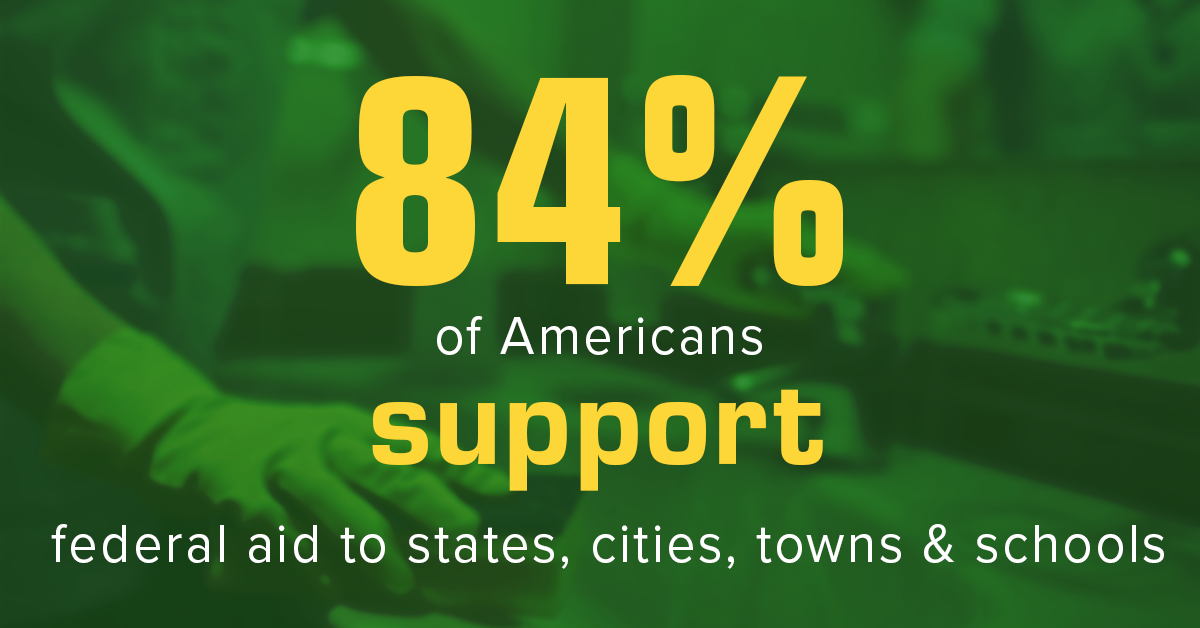

Providing federal aid to help states, cities, schools and towns fight this pandemic is widely supported by economists, health care professionals, state/local officials, and Americans on both sides of the aisle.

Some Republicans oppose aid to state and local governments; Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-KY) in the past has called such aid a “blue-state bailout.” Right now, that resistance is once again standing in the way of an urgently needed COVID relief package – despite the fact that children are falling behind in their education and state and local workers are needed to make sure people get aid they’re eligible for and vaccines as soon as possible.

In reality, reports the New York Times, the local and state budget crisis facing the U.S. is color blind. Six of the seven states expected to suffer the biggest revenue declines over the next two years are red – states led by Republican governors and carried this past November by President Trump.

“I don’t think it’s a red-state, blue-state issue,” Brian Sigritz, Director of State Fiscal Studies at the National Association of State Budget Officers told the Times.

The National Governors Association’s top leaders – Andrew M. Cuomo of New York, a Democrat, and Asa Hutchinson of Arkansas, a Republican, issued a statement this fall saying, “This is a national problem and it demands a national solution.”

Michael Leachman, Vice President for Fiscal Policy at the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, wrote a blog post last month in which he argued that the money provided to the states in the CARES Act – while helpful – was not nearly enough.

“After accounting for the federal aid provided to date, states will still face shortfalls of $350 billion to $490 billion through 2022,” he wrote. “If states draw down their rainy day funds, which totaled about $75 billion heading into the pandemic, they and other governments will still face shortfalls of about $275 billion to $415 billion.”

Moreover, Leachman wrote, these estimates likely understate the problem.

“For one thing, they don’t include states’ added costs to continue fighting the virus over the coming year,” he wrote. “The main form of aid to states and localities for this purpose, the Coronavirus Relief Fund in the CARES Act, expires on Dec. 30. But the virus very likely will remain a threat well into next year, forcing states to continue spending on protective equipment, testing, and other public health provisions, especially if cases surge over the winter.”

The Times reports that even the most optimistic assumptions about the course of the pandemic point to fiscal consequences for state and local governments that “would be the worst since the Great Depression” and take years to dig out of, according to Dan White, Director of Fiscal Research Policy at Moody’s Analytics.

Nowhere have the public-sector cuts been worse than in K-12 education. “There are about 570,000 fewer local education jobs” this year compared to the start of the previous school year, CBPP’s Leachman told NPR. “Those are teachers, bus drivers, cafeteria workers, secretaries, librarians, counselors.”

And remember: that could have been worse, had the CARES Act not included $13 billion for K-12.

“I think we’re about to see a school funding crisis unlike anything we have ever seen in modern history,” Rebecca Sibilia, the founder of EdBuild, a school finance advocacy organization, told NPR. “We are looking at devastation that we could not have imagined…a year ago.”

And the cuts, like almost everything else COVID-19-related, do not fall on all communities equally. The last time schools had to drastically cut budgets was immediately following the 2008 recession.

The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit online media outlet that focuses solely on education, recently reported on what happened then. It quoted a study that found that student achievement suffered in proportion to how much funding was cut. Specifically: the study calculated that a $1,000 reduction in per-pupil spending after the 2008 recession reduced reading and math scores by about 1.6 percentage points and college attendance by 2.6 percent.

Wealthy communities were more able to offset the state funding cuts by digging into reserves, raising taxes or charging fees. State budget cuts had the effect of increasing achievement gaps for both low-income students and students of color. A $1,000 spending cut increased the gap in test scores between Black and white students by 6 percent.

In a July briefing to education journalists, Hechinger notes, school finance experts explained why low-income children were harmed more by the 2008 funding cuts. Teacher union contracts often specify that layoffs must start with the most recently hired teachers, protecting veteran teachers with more seniority. Poor schools, where the conditions are more challenging, tend to have more junior teachers and fewer veterans so low-income communities bore the brunt of the teacher layoffs.

The bottom line? The 2008 recession affected all student learning but had a disproportionate impact on low-income students and students of color.

A similar case can be made that when massive cuts to public sector jobs occur, it is women and minorities that are most affected. State and local employees make up roughly 13 percent of the nation’s work force, the Times reports. For women and Black workers, in particular, the public sector has historically offered more opportunities than the private sector for a stable income and reliable benefits.

“These are folks that are providing essential public services every single day, risking their lives,” said Lee Saunders, President of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). “And now there’s a good possibility that many are going to be faced with a pink slip.”